Written by Abhilaasha Nagarajan, Consultant – Practice, IIHS.

Kannagi Nagar, a vibrant resettlement site in the south of Chennai, brims with stories. This bustling community is home to 15,000 households relocated due to river restoration efforts and the 2004 tsunami. As an urban researcher, I often frequent this place to understand its cultural mosaic. In one of our studies, IIHS team highlighted the issues in WaSH infrastructure and services prevalent here despite government efforts, such as irregular water supply, poor water quality, widespread waste dumping, and shared toilets.

“I wish my brother understood what I go through every month. Maybe if someone talked to him, things would change” – a poignant remark by a 13-year-old girl during our previous interactions on sanitation, drove me back to explore the untold MHM stories beneath the colourful facades of Kannagi Nagar. It’s inevitable to bump into familiar faces here, and Samu, a 24-year-old working in the e-commerce sector like other young men in the area, joined me in my search for stories. Upon sharing the purpose of my visit, he remarked, “This is not something everyone will speak to you about”. Nevertheless, determined to understand the community’s experiences in MHM, I requested Samu to take me to a few people. Thanks to our study, I already had some insights on how women manage their periods. This time, I decided to discover how other family members, especially men, perceived menstruation.

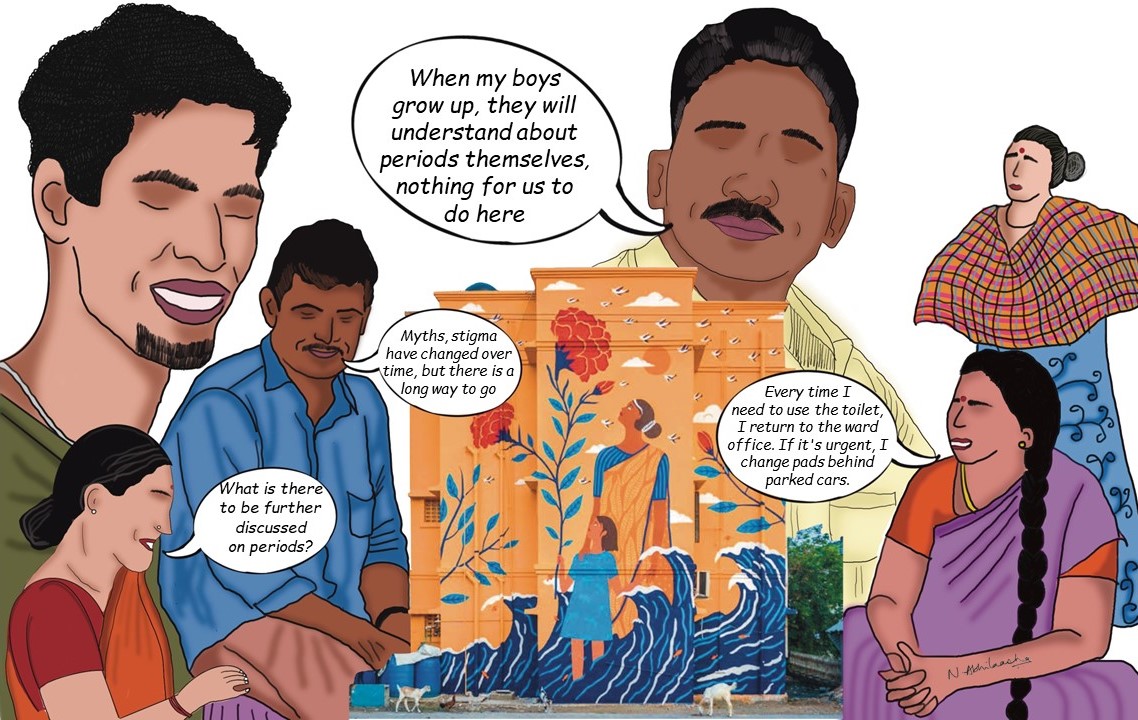

Most men I spoke with had learnt about periods only after marriage and did all or part of the household work during those times. However, few had little else to say and didn’t feel the need to learn more either. Kathir (41) said, “When my boys grow up, they will understand about periods themselves, nothing for us to do here”. Palani (47) added “It used to be all euphemisms, and we had a role to play in the puberty functions. Nothing else was discussed with us, it is a ‘ladies’ matter’”. However, digital media has significantly increased awareness among the younger generation. Samu said, “We see everything on reels these days, so we know about periods. I encourage the women around me to feel comfortable in sharing about having periods or dealing with pain. If men understand and acknowledge these challenges, it can make a big difference to women”. Listening to him, I recollected women and girls telling us that they missed paid work and school, and faced seclusion at home and social gatherings due to periods. Anbu (56) said, “Myths and stigma like ‘do not cook’, ’don’t go near puja room’ have changed over time, but there is a long way to go – for men and women”.

Velu (63) pointed out, “My wife used to wash and hang the cloth discretely in the toilet, but now my daughters use pads”. Yes, cloth was still preferred next to pads, despite inadequate space to dry them. Shared toilets too add to the challenge as it compromises privacy in washing and changing during periods. Indicating houses with shared toilets, Samu explained, “It is impossible to put a cover or dustbin in the shared toilet, as its cleaning will lead to fights between users. Usually, people rent entire portions for their family members, especially women and girls, to have access to a separate toilet”.

Once we toss away a used pad, its destiny often slips our mind. But for some, the trouble begins when the disposal takes a wrong turn. During a conversation with a group of sanitation workers near the ward office, Dileep (36) said, “Workers in middle- and high-income areas may receive segregated waste, but in places like Kannagi Nagar, residents dispose absorbents off in toilets and storm drains, making our job extremely difficult and unpleasant due to the heavy, foul-smelling waste. After struggling with such practices, I requested and eventually got transferred to another area in the same ward,”. But, Palani (45), from another ward, opined, “Whatever be the area, waste segregation is followed only by a few houses, though at the Micro Composting Centre, we take it seriously. We sort items like diapers and pads together, wearing gloves and masks. Our jobs become harder when households delay in handing over their waste by 3-4 days”.

Balancing their menstrual health while dealing with menstrual waste makes things more challenging for female workers. Lack of proper menstrual facilities led many women to miss work and lose income. Iniya (34), a night sweeper, shared her plight, “We have no support during our periods. At nights, public toilets are mostly closed. Every time I need to use the toilet, I return to the ward office with the e-cart driver. If it’s urgent, I take a leak, and change pads behind parked cars. I can’t ask any house for help, because I know they won’t even give us water”. According to NFHS-5, around 22% of young urban women lack access to menstrual products, and older and poorer women have greater hurdles. Chinnama (41) expressed her discomfort in openly discussing ‘periods’ with her male supervisors, and preferred euphemisms like ‘stomach pain’. Iniya further revealed that her male peers were reluctant to handle what they perceived as “women waste”, prompting a few to seek change in shifts.

Trudging on with Samu and contemplating the invisible challenges of menstrual health, I realised why he was apprehensive about my idea of discussing ‘periods’ with the residents. It is evident that the stigma surrounding MHM cascades through families, workplaces, and communities but these societal attitudes cannot solely be attributed to men. Many women were also amused, “What is there to be further discussed on ‘periods’?”.

As I left Kannagi Nagar, its voices echoed in my mind. Periods are not just about bleeding, it has broader impact on women’s reproductive health and overall well-being. While women consider men as allies during menstruation, conversations with men rarely broach the topic. It is irrefutable that more awareness is essential by empowering women to share their experiences and encouraging men to participate meaningfully to achieve a #PeriodFriendlyWorld.

Let’s normalise period conversations, strive for accessible menstrual products, and ensure safe, supportive environment for all. Together, we can break taboos, dispel myths, and create a world where menstruation is celebrated. As the conservationist Jane Goodall said, “change happens by listening and then starting a dialogue with the people who are doing something you don’t believe is right”. Let’s break the silence and start the conversation.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes out to the residents of Kannagi Nagar for their time and openness in sharing their stories and experiences with me. All names have been changed to protect their privacy.

Special thanks to Niladri Chakraborti for the invaluable insights and feedback, which played a crucial role in shaping the final piece.

Pictures shot by Prasanth K, Niki Nirvikalpa, Sadhana B and Abhinaya Pereppi.

Content edited by Sakthi Sangeetha.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.